Dr. Mohamed Najim

Director of Research Laboratory

University Professor in Signal and Image Processing at the Polytechnic Institute and University of Bordeaux

Co-author of the book “When Wine Makes Its Revolution”

In the world of wine, there are extraordinary enthusiasts, and Mohamed Najim is a perfect example. Born in Morocco in 1945, this engineer graduated from the National Higher School of Electronics, Computer Science, and Telecommunications of Bordeaux (ENSEIRB) and a doctorate in science from the University of Toulouse. He is a reference in the scientific world for the excellence of his work, as well as for his deep knowledge of French wines.

With a diverse teaching experience from a geographical perspective, Mohamed Najim joined the University of Rabat as a professor in 1972, was a visiting professor at the University of Berkeley in 1983, founded ENSIAS, a school of computer engineering and systems analysis in Rabat in 1985, and held the first chair in signal and image processing at the Bordeaux Campus in 1988.

In 2021, Mohamed Najim co-authored the book “The Wine Revolution,” born from an idea of his friend Etienne Gingembre. This book unfolds like a saga, an immersion in the land, an innovative exploration across France. It also offers a reflection on the spiritual dimension that the world of spirits can embody. This work on the wine revolution is both a poignant narrative of humanity and an essential guide, accompanied by a selection of the best young winemakers

Your journey

Gerda: You have a scientific background, but how did your passion for wine come about?

Mohamed Najim: I grew up in Morocco during the French protectorate period when the French were producing wine. My parents were land-owners, and our neighbours had vineyards. So, I witnessed my first grape harvest in Morocco when I was 4 or 5 years old.

My family didn’t drink wine, but they were tolerant in many ways. I started drinking wine when I arrived in France for my studies in 1963.

At university, they even sold quarter bottles, that type of wine that stains, truly another era! I really began to appreciate wine after the events of 1968, when I met my wife, who is from Gers. One of her uncles produced wine. In 1972, I returned to Morocco and managed to buy a little wine directly from the producer there, but I didn’t have in-depth knowledge. My wife had to return to France, and for 2 years, I commuted between Morocco and France. While consulting Air France magazine on the plane, I discovered the existence of Primeur wines.

I thought, “Oh, this must be something extraordinary; I must buy Primeur wines.” When you come from far, you often dream of prestigious wines like Château Margaux. I didn’t know anyone who could advise me. So, I decided to write a handwritten letter, which I still have, to Château Margaux. Then, I received a letter from them on glossy paper from Paris. They provided me with the names of 4 wine merchants.

I called the first one who said, “No, we don’t sell to individuals, but how many pallets do you want?” I didn’t even know how many bottles were in a pallet. Eventually, I called Madame Descaves, whose name had also been given to me. I said to her: “I have just arrived, I know nothing about wine, but I want to buy 6 bottles of Château Margaux.” She said, “We only sell by the case of 12.” I replied, “That’s okay, I’ll take that case, and I’ll share it with a friend.” When I went to see her, she said, “My dear, the price per bottle is 250 Frf (38€) excluding tax.”

She was the one who advised me on building my wine cellar. I gradually learned through trial and error. Sometimes, I wrote to the owners to get allocations, and they granted them to me. I was very lucky in this regard. Thanks to these efforts, I was able to meet many great producers, and gradually my passion developed when I settled permanently in Bordeaux. In 1988, I became a member of brotherhoods in Burgundy and Bordeaux. Wine is an extraordinary product of conviviality; I am aware that wine is closely linked to emotion and sharing.

G: What motivated you to write a book about the wine revolution in France?

MN:The idea for the book comes from my friend Etienne Gingembre, whom I have known for 25 years. His knowledge of wine was much broader than mine. He opened doors for me, and little by little, we got caught up in the game of tastings. He lives in Paris and knows the publishing houses well. One day, he said to me, “Mohammed, I have been asked for a book, and I thought you could be my co-author.” It was during the pandemic. We worked for three months full-time, 12 hours a day, and we called each other four times a day.

With this book, we are not only addressing Bordeaux but also other regions. It reflects French plurality. In this work, we explore the major revolution that is quietly but inevitably taking place. From terroir to grape variety, from pruning to harvest, from vinification to marketing, everything is in motion. We are witnessing an unprecedented transformation over the past 8,000 years in one of the anthropological and fundamental pillars of our agriculture, culture, technical know-how, and way of life. This book unfolds like a saga, an immersion in the land, an innovative exploration across France. It also offers a reflection on the spiritual dimension that the world of spirits can embody. This work on the wine revolution is both a poignant narrative of humanity and an essential guide, accompanied by a selection of the best young winemakers.

The Wine Revolution

G: In the book “La Révolution du Vin”, you talk about an unprecedented change in the wine world over the last 8,000 years. What are the main challenges facing Bordeaux in the coming years?

MN: Bordeaux faces several challenges, both internal and external. As stoic philosophy suggests, it’s important to focus on what we can control, while the rest must be accepted. One aspect we cannot control is the uprooting of vines, an extremely regrettable situation in Bordeaux. Small winegrowers are unable to make a living from their work, which is a real tragedy.

This situation is due to several factors. Firstly, there’s the phenomenon of “Bordeaux Bashing.” Bordeaux is often associated with expensive wines, and many restaurants worldwide refuse to include Bordeaux wines on their menu. This is a prejudice because we produce some magnificent wines in a price range of 10 to 15 euros, such as Côtes de Castillon, Fronsacs, and even some Crus Bourgeois in the Médoc. Yet, these wines don’t find their place on restaurant tables. There’s a boomerang effect between the extreme fame of the Grand Crus, which now has negative repercussions on small producers. Bordeaux hasn’t been able to anticipate this effect compared to other wine regions. It’s an internal tragedy.

On the other hand, there’s the challenge beyond our control, namely climate change, which could radically alter the region. However, what concerns me most right now is the situation of small winegrowers struggling to make a living from their production.

Today, there are two attitudes towards farmers and the land in general. While some wrongly or rightly believe they contribute to climate change, it’s unfair for the responsibility to solely fall on them. The burden should be shared across society. We shouldn’t adopt a harsh approach towards them; society as a whole must share this responsibility. However, achieving this distribution requires mobilization, proactive action that no one is willing to undertake because it concerns the long term, and unfortunately, we’re often focused on short-term actions. We’ve already seen a decrease in the number of farmers and a concentration/industrialization of this profession. This phenomenon is painful, and what we observe constitutes human tragedies before our eyes.

G: In 2011, you were one of three scientists worldwide to be awarded the prize of the International Academy of Sciences, whose main aim is to promote scientific skills with a view to sustainable development in the countries of the South. In your opinion, is it compulsory for a great wine to be organic? Or does everyone do as they please?

MN: I believe one must be convinced to succeed in this approach. Consumer choice will encourage owners to embark on this path. However, it will be difficult to steer all properties in this direction. For those who have already adopted this approach and use harmful inputs, measures are needed, not only coercive but also educational, to help them reduce the use of harmful products. I think regulation will naturally come into play. Many large properties are opting for organic, such as Latour and Lafite Rothschild, which are in the process of transitioning. There’s work to return to nature and allow it to express itself without excessive human intervention. However, I don’t think being organic is mandatory for a grand cru. Everyone should be free to make their own choices, but it’s important to encourage and support those who choose to embark on this path.

G: You mention the influence of Robert Parker. What do you think of wine rating systems today?

MN: Today, we observe a plurality of ratings. These systems have had both positive and negative effects. Parker has contributed to making Bordeaux and French wines known. Now, enthusiasts are much more informed. The sharp expertise of Parker and others is now widely disseminated worldwide, especially through social networks. Wine is not an algorithm or a mathematical equation. My appreciation of a wine at a given moment depends on my palate, my current emotion. Thus, I could rate a wine an 18 while another person, in a different emotional state, could give it a 16. It’s very difficult to give an objective rating to a wine. However, I don’t want to criticize those who assign ratings because they provide benchmarks for those who cannot taste the wine themselves

“Quand le Vin Fait Sa Révolution”

de Mohamed Najim & Etienne Gingembre paru en 2021 aux Editions le Cerf à Paris

Bordeaux Wines

G: Does Bordeaux still have a lot of assets?

MN :I may be partial because I live in Bordeaux, but I think that yes, we have many assets. We have a diverse range of wines, from €8 to €5,000, offering emotions that you can’t find anywhere else. People don’t just ask for a Chardonnay, they ask for a Bordeaux. However, Bordeaux lacks aggression on the international stage. We could do more to make Bordeaux better known, better recognised and better at promoting its know-how, even for ‘small’ producers. Even the Place de Bordeaux is in crisis, because the added value that can be realised by buying en Primeur wines has been considerably reduced. Everyone has to contribute to making Bordeaux shine.

This extreme concentration in the world of wine, which has turned it into a luxury product, is having a negative effect. Producing luxury wines is a good thing because it confers a certain notoriety, but on the other hand, it reinforces the idea that Bordeaux wines are expensive and this alienates the average consumer. So it’s important to strike a balance between producing luxury wines and promoting wines that are accessible to all budgets.

Bordeaux has a large and very diverse university cluster, ranging from legal studies to the sciences. It has a wealth of expertise, and the Institut des Sciences de la Vigne et du Vin (ISVV) is a leading institution in Bordeaux, the region and the world.

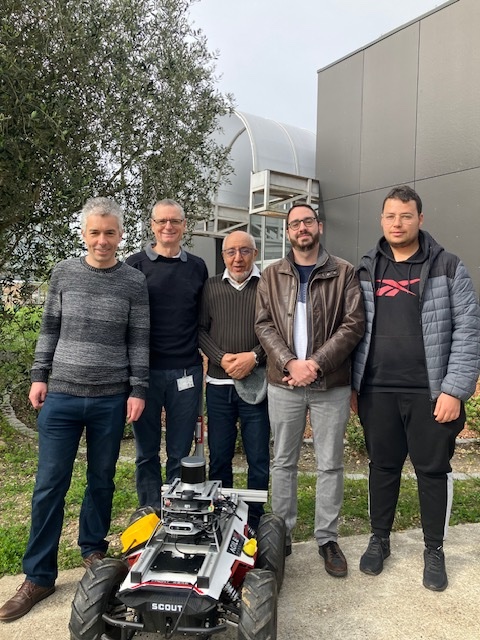

At our university, we are working on signal and image processing to detect vine diseases using artificial intelligence tools. Our aim is to make this image processing available to the environment and the socio-economic sector. Bordeaux is world-renowned for its expertise in this field, and its ability to attract and develop its regional wealth is remarkable. However, it is important to continue to innovate and develop in order to maintain this leading position and meet the current and future challenges facing the wine industry

Institut polytechnique de Bordeaux team behind the robot scout

Bottle of exception

GB: What, in your opinion, characterises an exceptional bottle?MN: For me, an exceptional bottle is much more than just a beverage. It’s a sensory and emotional experience that engages all the senses. First of all, there’s the bottle itself and its surroundings. The emotion you feel when tasting wine can be multiplied depending on the people with whom you share the moment. So there’s both the intrinsic quality of the bottle and the sharing experience that accompanies it. You can feel a certain osmosis with your tasting companions, be happy, and see in their eyes a form of recognition for having shared this moment with them. For me, savouring an exceptional bottle arouses emotions, even subconsciously.

Then there’s the wine itself. An exceptional bottle must have a unique personality and an aromatic complexity that evolves over time. It must also have a certain harmony and balance between its different components, such as acidity, tannin, fruit and wood. You think of the people who created it, who for me are true artists who can succeed, but also fail. Shaping a wine is an art, and the consultants add a note to the score by bringing a diversity of perspectives. Everyone brings their own sensibility and their own way of doing things, and among them there are self-taught people like Stephane Derenoncourt and others who have undergone training, and this is reflected in the wine.

Tomorrow

G: Finally, wine has undergone its own revolution, as you and Etienne Gingembre have written, but what do you think its future will be?

MN: Despite this revolution, the future of wine remains uncertain. Consumption has fallen considerably and we’re seeing a change in the way wine is perceived. Once seen as a simple pleasure to taste, wine is now perceived as a complex universe that requires an initiation. The language we use can be discouraging for the new generation. Perhaps we don’t teach young people enough, and they lose interest in our overly complex descriptions.

For a neophyte, tasting wine boils down to liking it or not liking it. So it’s important to offer a wine that feels good from the first sip.

Bordeaux is fascinating, but it is also very complex. The average consumer in the street is not necessarily aware of the great complexity of the terroirs, appellations, côtes, etc. They have difficulty with labelling and often find themselves lost. However, all this complexity is the richness of our region and it is important to preserve its personality.

Today, very large producers from all over the world are flooding the market, contributing to the standardisation of tastes. For a winegrower with just 15 hectares? it’s difficult to achieve an international dimension. Bordeaux is thus faced with a complex situation in which human wealth and diversity are becoming a handicap.

Gerda BEZIADE has an incredible passion for wine, and possesses a perfect knowledge of Bordeaux acquired within prestigious wine merchants for 25 years. Gerda joins Roland Coiffe & Associés in order to bring you, through “Inside La PLACE” more information about the estate we sell.